Chapter II: Clowns, Poets, and Circus Daredevils

Section 1 - Poetry

Section 2 - Images

Section 3 - Music

The circus was a source of perpetual fascination for Debussy's artistic cohort, and paintings and poems pay homage in abundance. The consummate daring of the acrobats, the mercurial complexity of the clowns, the quicksilver nature of the entertainment, and the existence of a tight community outside society's norms all drew late 19th and early 20th century artists to the show.

The Fifth Duino Elegy (1923)

By Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926)

Rilke was German, but he lived in Paris from 1902-1910 and was heavily influenced by its popular culture. This poem draws specifically on Picasso's painting, "Family of Saltimbanques."

Who are these rambling acrobats,

less secure than even we;

twisted since childhood

(for benefit of whom?)

by an unappeasable will?

A will which wrings, bends,

swings, twists and catapults,

catching them when they fall

through slick and polished air

to a threadbare carpet worn

ever thinner by their leaping:

lost carpet of the great beyond,

stuck like a bandage to an earth

bruised by suburban skies.

Ensemble,

their bodies trace a vague

capital "C" for Creation...

captured by an inevitable grip

which bends even the mightiest,

as King Augustus the Strong

folded a pewter plate for laughs.

Around this center

the Rose of Looking

blossoms and sheds.

Around this pounding pestle,

this self pollinating pistle

producing petals of ennui,

blooms of customary apathy

speciously shine with

superfluous smiles.

There: the wrinkled, dried up Samson,

becomes, in old age, a drummer-

too small for the skin which looks

as though it once held two of him.

The other must be dead and buried

while this half fares alone,

deaf and somewhat addled

within the widowed skin.

There: the young man who seems

the very offspring of a union

between a stiff neck and a nun,

braced and buckled,

full of strength and

innocent simplicity.

O, you, children,

delivered to the infant Pain

as a toy to amuse it,

during some extended

illness of its childhood.

You, boy, discover

a hundred times a day

what green apples know,

dropping off a tree created

through mutual interactions

(coursing through spring,

summer and, swift as water,

fall, all in a flash)

to bounce, thud, upon the grave.

Sometimes, in fleeting glances

toward your seldom tender mother,

affection almost surfaces,

only to submerge as suddenly

beneath your face...a shy,

half-tried expression...

and then the man claps,

commanding you to leap again

and before any pain can

straddle your galloping heart,

your stinging soles outrace it,

chasing a brief pair of

actual tears to your eyes,

still blindly smiling.

O angel, pluck that

small flower of healing!

Craft a vessel to contain it!

Set it amongst joys not

yet vouchsafed us.

Upon that fair herbal jar,

in flowing, fancy letters,

inscribe: "Subrisio Saltat."

...Smile of Acrobat...

And you, little sweetheart,

silently overlept by

the most exciting joys-

perhaps your skirthems

are happy in your stead,

or maybe the green metallic silk,

stretched tight by budding breasts,

feels itself sufficiently indulged.

You,

displaying, for all to see,

the fruit which tips the

swaying scales of balance,

suspended from the shoulders.

Where...O where is that place,

held in my heart, before they'd

all achieved such expertise,

were apt still to tumble asunder

like poorly fitted animals mating...

where the barbell still seems heavy,

where the discus wobbles and topples

from a badly twirled baton?

Then: Presto! in this

exasperating nowhere:

the unspeakable space appears where

purity of insufficiency transforms

into overly efficient emptiness.

Where the monumental bill of charges,

in final arbitration, totals zero.

Plazas, O plazas of Paris,

endless showcase, where

Madame Death the Milliner

twists and twines the

ribbons of restlessness,

designing ever new frills,

bows, rustles and brocades,

dyed in truthless colors,

to deck the trashy

winter hats of fate.

Angel! Were there an unknown place

where, upon an uncanny carpet, lovers

could disport themselves in ways

here inconceivable-daring ariel maneuvers

of the heart, scaling high plateaus of passion,

ladders leaning one against the other,

planted trembling upon the void...

Were there such a place, would their

performance prove convincing to an audience

of the innumerable and silent dead?

Would not these dead toss down their

final, hoarded, secret coins of joy,

legal tender of eternity, before the

couple smiling on that detumescent carpet,

fully satisfied?

English translation by Robert Hunter.

Baudelaire, father of the French symbolist poets, wrote here, in one of his most famous prose poems, about the tragic fate of an old and forgotten acrobat.

Le vieux saltimbanque (The Old Mountebank)

By Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867)

Everywhere the holiday crowd was parading, spread out, merry making. It was one of those festivals on which mountebanks, tricksters, animal trainers and itin-erant merchants had long been relying, to compensate for the dull seasons of the year.

Partout s'étalait, se répandait, s'ébaudissait le peuple en vacances. C'était une de ces solennités sur lesquelles, pendant un long temps, comptent les saltimbanques, les faiseurs de tours, les montreurs d'animaux et les boutiquiers ambulants, pour compenser les mauvais temps de l'année.

On such days it seems to me the people forget all, sad¬ness and work; they become children. For the little ones, it is a day of leave, the horror of the school put off twenty-four hours. For the grown-ups, it is an armistice, concluded with the malevolent forces of life, a respite in the universal contention and struggle.

En ces jours-là il me semble que le peuple oublie tout, la douceur et le travail; il devient pareil aux enfants. Pour les petits c'est un jour de congé, c'est l'horreur de l'école renvoyée à vingt-quatre heures. Pour les grands c'est un armistice conclu avec les puissances malfaisantes de la vie, un répit dans la contention et la lutte universelles.

The man of the world himself, and even he who is occupied with spiritual tasks, with difficulty escape the influence of this popular jubilee. They absorb, without volition, their part of the atmosphere of devil-may-care. As for me, I never fail, like a true Parisian, to inspect all the booths that flaunt themselves in these solemn epochæ.

L'homme du monde lui-même et l'homme occupé de travaux spirituels échappent difficilement à l'influence de ce jubilé populaire. Ils absorbent, sans le vouloir, leur part de cette atmosphère d'insouciance. Pour moi, je ne manque jamais, en vrai Parisien, de passer la revue de toutes les baraques qui se pavanent à ces époques solennelles.

They made, in truth, a formidable gathering: they bawled, bellowed, howled. It was a mingling of cries, of blaring of brass and bursting of rockets. The clowns and the simpletons convulsed the features of their swarthy faces, hardened by wind, rain, and sun; they hurled forth, with the assurance of comedians certain of their wares, witticisms and pleasantries of a humor solid and heavy as that of Moliere. The Hercules, proud of the enormousness of their limbs, without forehead, with¬out cranium, stalked majestically about under fleshings fresh washed for the occasion. The dancers, pretty as fairies or as princesses, leapt and cavorted under the flare of lanterns which filled their skirts with sparkles.

Elles se faisaient, en vérité, une concurrence formidable: elles piaillaient, beuglaient, hurlaient. C'était un mélange de cris, de détonations de cuivre et d'explosions de fusées. Les queues-rouges et les Jocrisses convulsaient les traits de leurs visages basanés, racornis par le vent, la pluie et le soleil; ils lançaient, avec l'aplomb des comédiens sûrs de leurs effets, des bons mots et des plaisanteries d'un comique solide et lourd comme celui de Molière. Les Hercules, fiers de l'énormité de leurs membres, sans front et sans crâne, comme les orangs-outangs, se prélassaient majestueusement sous les maillots lavés la veille pour la circonstance. Les danseuses, belles comme des fées ou des princesses, sautaient et cabriolaient sous le feu des lanternes qui remplissaient leurs jupes d'étincelles.

All was light, dust, shouting, joy, tumult; some spent, others gained, the one and the other equally joyful. Children clung to their mothers' skirts to obtain a sugar stick, or climbed upon their fathers' shoulders the better to see a conjurer dazzling as a god. And spread over all, dominating every odor, was a smell of frying, which was the incense of the festival.

Tout n'était que lumière, poussière, cris, joie, tumulte; les uns dépensaient, les autres gagnaient, les uns et les autres également joyeux. Les enfants se suspendaient aux jupons de leurs mères pour obtenir quelque bâton de sucre, ou montaient sur les épaules de leurs pères pour mieux voir un escamoteur éblouissant comme un dieu. Et partout circulait, dominant tous les parfums, une odeur de friture qui était comme l'encens de cette fête.

At the end, at the extreme end of the row of booths, as if, ashamed, he had exiled himself from all these splendors, I saw an old mountebank, stooped, decrepit, emaciated, a ruin of a man, leaning against one of the pillars of his hut, more wretched than that of the most besotted barbarian, the distress of which two candle ends, guttering and smoking, lighted up only too well.

Au bout, à l'extrême bout de la rangée de baraques, comme si, honteux, il s'était exilé lui-même de toutes ces splendeurs, je vis un pauvre saltimbanque, voûté, caduc, décrépit, une ruine d'homme, adossé contre un des poteaux de sa cahute; une cahute plus misérable que celle du sauvage le plus abruti, et dont deux bouts de chandelles, coulants et fumants, éclairaient trop bien encore la détresse.

Everywhere was joy, gain, revelry; everywhere certainty of the morrow's bread; everywhere the frenetic outbursts of vitality. Here, absolute misery, misery bedecked, to crown the horror, in comic tatters, where necessity, rather than art, produced the contrast. He was not laughing, the wretched one! He was not weeping, he was not dancing, he was not gesticulating, he was not crying. He was singing no song, gay or grievous, he was imploring no one. He was mute and immobile. He had renounced, he had withdrawn. His destiny was accomplished.

Partout la joie, le gain, la débauche; partout la certitude du pain pour les lendemains; partout l'explosion frénétique de la vitalité. Ici la misère absolue, la misère affublée, pour comble d'horreur, de haillons comiques, où la nécessité, bien plus que l'art, avait introduit le contraste. Il ne riait pas, le misérable! Il ne pleurait pas, il ne dansait pas, il ne gesticulait pas, il ne criait pas ; il ne chantait aucune chanson, ni gaie ni lamentable, il n'implorait pas. Il était muet et immobile. Il avait renoncé, il avait abdiqué. Sa destinée était faite.

But what a deep, unforgettable look he cast over the crowd and the lights, the moving stream of which was stemmed a few yards from his repulsive wretchedness! I felt my throat clutched by the terrible hand of hysteria, and it seemed as though glances were clouded by rebellious tears that would not fall.

Mais quel regard profond, inoubliable, il promenait sur la foule et les lumières, dont le flot mouvant s'arrêtait à quelques pas de sa répulsive misère ! Je sentis ma gorge serrée par la main terrible de l'hystérie, et il me sembla que mes regards étaient offusqués par ces larmes rebelles qui ne veulent pas tomber.

What was to be done? What good was there in asking the unfortunate what curiosity, what marvel had he to show within those barefaced shades, behind that threadbare curtain? In truth, I dared not; and, although the reason for my timidity will make you laugh, I confess that I was afraid of humiliating him. At length, I had resolved to drop a coin while passing his boards, in the hope that he would divine my purpose, when a great backwash of people, produced by I know not what disturbance, carried me far away.

Que faire? A quoi bon demander à l'infortuné quelle curiosité, quelle merveille il avait à montrer dans ces ténèbres puantes, derrière son rideau déchiqueté? En vérité, je n'osais; et, dût la raison de ma timidité vous faire rire, j'avouerai que je craignais de l'humilier. Enfin, je venais de me résoudre à déposer en passant quelque argent sur une de ses planches, espérant qu'il devinerait mon intention, quand un grand reflux de peuple, causé par je ne sais quel trouble, m'entraîna loin de lui.

And leaving, obsessed by the sight, I sought to analyze my sudden sadness, and I said: "I have just seen the image of the aged man of letters, who has survived the generation of which he was the brilliant entertainer; of the old poet, friendless, without family, without child, degraded by his misery and by public ingratitude, into whose booth a forgetful world no longer wants to go!"

Et, m'en retournant, obsédé par cette vision, je cherchai à analyser ma soudaine douleur, et je me dis: Je viens de voir l'image du vieil homme de lettres qui a survécu à la génération dont il fut le brillant amuseur; du vieux poète sans amis, sans famille, sans enfants, dégradé par sa misère et par l'ingratitude publique, et dans la baraque de qui le monde oublieux ne veut plus entrer!

English translation reprinted from Baudelaire, his prose and poetry, ed. by T. R. Smith, 1919.

Danville's poem about a clown/acrobat who jumps higher and higher, eventually breaking through to the stars, is a nice symbolic rendering of the artistic ideal of achieving eternal life through super-human feats of daring and courage.

Le saut du tremplin, from Odes funambulesques (1873)

By Théodore Banville (1823-1891)

Clown admirable, en vérité!

Je crois que la postérité,

Dont sans cesse l'horizon bouge,

Le reverra, sa plaie au flanc.

Il était barbouillé de blanc,

De jaune, de vert et de rouge.

Même jusqu'à Madagascar

Son nom était parvenu, car

C'était selon tous les principes

Qu'après les cercles de papier,

Sans jamais les estropier

Il traversait le rond des pipes.

De la pesanteur affranchi,

Sans y voir clair il eût franchi

Les escaliers de Piranèse.

La lumière qui le frappait

Faisait resplendir son toupet

Comme un brasier dans la fournaise.

Il s'élevait à des hauteurs

Telles, que les autres sauteurs

Se consumaient en luttes vaines.

Ils le trouvaient décourageant,

Et murmuraient: " Quel vif-argent

Ce démon a-t-il dans les veines ?"

Tout le peuple criait: "Bravo!"

Mais lui, par un effort nouveau,

Semblait roidir sa jambe nue,

Et, sans que l'on sût avec qui,

Cet émule de la Saqui

Parlait bas en langue inconnue.

C'était avec son cher tremplin.

Il lui disait: "Théâtre, plein

D'inspiration fantastique,

Tremplin qui tressailles d'émoi

Quand je prends un élan, fais-moi

Bondir plus haut, planche élastique!

"Frêle machine aux reins puissants,

Fais-moi bondir, moi qui me sens

Plus agile que les panthères,

Si haut que je ne puisse voir,

Avec leur cruel habit noir

Ces épiciers et ces notaires!

"Par quelque prodige pompeux

Fais-moi monter, si tu le peux,

Jusqu'à ces sommets où, sans règles,

Embrouillant les cheveux vermeils

Des planètes et des soleils,

Se croisent la foudre et les aigles.

Jusqu'à ces éthers pleins de bruit,

Où, mêlant dans l'affreuse nuit

Leurs haleines exténuées,

Les autans ivres de courroux

Dorment, échevelés et fous,

Sur les seins pâles des nuées.

"Plus haut encor, jusqu'au ciel pur!

Jusqu'à ce lapis dont l'azur

Couvre notre prison mouvante!

Jusqu'à ces rouges Orients

Où marchent des Dieux flamboyants,

Fous de colère et d'épouvante.

"Plus loin! plus haut! je vois encore

Des boursiers à lunettes d'or,

Des critiques, des demoiselles

Et des réalistes en feu.

Plus haut! plus loin! de l'air! du bleu!

Des ailes! des ailes! des ailes!"

Enfin, de son vil échafaud,

Le clown sauta si haut, si haut

Qu'il creva le plafond de toiles

Au son du cor et du tambour,

Et, le coeur dévoré d'amour,

Alla rouler dans les étoiles.

The Zemganno Brothers is the quintessential circus novel of ambition, daring, and ultimate tragedy. In the excerpt below, Nello, who has been irremediably injured in his attempt at a superhuman feat, recounts his nightmare vision of the circus to Gianni, his brother and life-time circus partner. The novel is, to this day, thrilling: a testimony to the power and allure of physical and mental exploits that push human endurance beyond its natural limits.

Les frères Zemganno (The Zemganno brothers) (1879)

By Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896)

The sedative which Nello took each night contained opium which disturbed his sleep and gave him nightmares.

One night he dreamed that he was at the Circus. At least, he thought it was the Circus, and yet it was not, which often happens in dreams, when, strange though it seems, we imagine ourselves in places we know, but which have lost their identity and are completely transformed. Well, what Nello dreamed was that one day the Circus had swollen to a fantastic size, and the spectators, sitting on the far side of the ring, looked as if they were a quarter of a mile away, for everything was blurred, and they had no faces. The chandeliers were sprouting a whole army of other chandeliers, so many, in fact, that they could not be counted. Each light had a very curious quality, rather like that thrown by a candle in a mirror.

An Orchestra filled the whole theatre, and the players threw themselves about all over the place as if they were demons; no sounds came from the violins or the brass. The only things in that vast space were the bodies of tiny children circling at breakneck speed round the feet of men, the rest of whose bodies were invisible; careering droves of horses with riders clutching hold of their tails, streaming in the wind; parabolas of gymnasts, who never crashed to earth but floated like ethereal beings. Stretching into the distance ran never-ending lines of trapezes, over which somersaults were being made for ever and ever. There were also innumerable avenues of paper hoops, through which veiled women leapt unceasingly, while from the tops of giddy prominences as high as Notre-Dame, rope dancers jigged to earth, with inscrutable faces.

All this got muddled up, and then, when the gaslight died away, it all faded; in a trice, a thousand clowns, garbed in black with skeletons embroidered in white silk on their skin-tight costumes, tumbled into the circus-ring. Pieces of black paper were struck inside their gashed mouths, as if every clown had several teeth missing. Each buffoon hung on to the tail of the one in front of him, and they all balanced themselves with exactly the same posture and at exactly the same moment; then, weaving in and out like a long snake, coiled round the ring. Marble columns sprang out of the earth, and the regiment of clowns was now seen again, each clown sitting on top of a column. There they squatted on their tailends, hands placed flat on the soles of their feet, which had been raised at either side of their heads; they looked, those powdered enigmatic sphinxes, at the audience from between their legs.

The gas flared into life again, and, as the light returned, vitality flowed back into the faces of the ghost-like spectators; in a twinkling the black clowns vanished.

In the midst of all that leaping, flying and jumping, where spangles lit the sky like shooting stars, everything seemed to be swaying. This was a new fantastic world, where every creature was boneless, where rubber limbs could have been tied into knots, as if they were ribbons, a nightmare of giants who could be folded up and crammed into boxes all in one piece—a phantasmagoria of every impossible, impracticable thing done by the human body.

Mingling with all these frightening fantasies, were things that Nello thought he had seen before, and things his brother had read to him. It was a dream of kaleidoscopic confusion. Here came an Indian juggler, who, by some miracle, was able to keep his balance, perched on the sconce of a slender, gigantic two-branched chandelier. And there, a modern Hercules, who lifted a huge omnibus by its footboard with his teeth. Next, an old-timer of an acrobat, who leapt about madly and hopped on one leg on to a big-bellied leafier bottle, and then an elephant, dancing like a fairy on a high wire.

The gas died down again, and the black clowns came back into the picture for a short while, still squatting on the tops of their columns.

The show started up once more. But this time it pursued its course in light which took the colour out of everything, where every object reflected the hard glassy faces and bodies as if engraved in Venetian mirrors. The whole spectacle had now transformed itself into one huge, pale, false world, full of women's legs, men's arms, children's bodies, horses' rumps, and elephants' trunks, a perpetual wheeling circle of limbs, muscles, humans and animals, and as everything began to get faster and faster, the sleeper felt that his whole body was worn out and drenched with pain.

"Are you still in pain tonight?" said Gianni, going into his brother's bedroom.

"No," said Nello, "No… but I think I've had a raging fever… and then, such horrible dreams."

And Nello told his brother about the nightmare.

"Yes," he went on, "just think of it… there I was, sitting exactly where I sat that first evening in Paris… you remember it, don't you?... that place low down on the left, right by the exit… isn't it odd?... but that's not the strangest thing about it… when everybody came back into the circus… they looked at me with an expression on their blurred faces which, in my dream, was most malevolent… as if they wanted to harm me… and that's not all... there were all those clowns, quite near to me… it was all over in a flash… then there was some poster or other, which I tried to read… but I couldn't see it very clearly… I can see it better now… and there I was, in my clown's costume… with those crutches you ordered for me yesterday."

Nello said no more, and Gianni stood stock-still for one long, sad moment, absolutely tongue-tied.

Translated by Leonard Clark and Iris Allam, (London: Alvin Redman, 1957) p. 182-185

(Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright; the publishing house of Alvin Redman no longer exists.)

General Lavine would have long disappeared from the annals of history were it not for Debussy's delightful Prelude (Prelude No. 6 from Book 2, "General Lavine"- excentric- ) evoking his stunts. The following is a long narrative recounting his history from a proud home state newspaper. It gives far more information about this mysterious character than I've encountered in any other source.

Article reprinted from the "This World" section of the San Francisco Chronicle, March 11, 1945

A Curious Literary Progress From Man to Mechanism

Alfred Frankenstein

Whenever you look at a campaign ribbon on a soldier’s chest you are, in all probability, inspecting the handiwork of the only human being, living or dead, of whom Claude Debussy composed a musical portrait. Today Edward La Vine lives in the desert town of Twentynine Palms, Cal., hard by the Joshua Tree National Monument, and calmly manufactures most of the “service bars” that are used in the Army, but when Debussy wrote about him he was one of the most celebrated figures in international vaudeville. He was a comic juggler, half tramp and half warrior but more tramp than warrior, and he was billed as “General Ed La Vine, the Man Who Has Soldiered All His Life.” Debussy immortalized him in his second book of preludes under the name of “General Lavine, Eccentric.”

A curious sequence of accidents has served to disembody General La Vine – or Lavine – in the literature. The books all make him out to be a marionette and not a human being at all. His literary progress from man to mechanism provides an instructive study in the consequences of careless translation.

The earliest mention of Debussy’s piece in the literature is in the article on the French composer’s piano music which Alfred Cortot contributed to the Debussy memorial number of the Revue Musicale in 1920. I give it as translated by Hilda Andrews for the English edition of Cortot’s collected essays, published in 1932:

“General Lavine, Eccentric. Here is all the incisive irony and verve of a Toulouse-Lautrec. It is the same old puppet that one has seen so often at the Folies-Bergere, with his coat several sizes too large and his mouth like a gaping scar, cleft by the set, beatific smile. And above all the ungainly skip of his walk, punctuated by the carefully stage-managed mishaps, and suddenly ended, like a released spring, by an amazing pirouette.”

Next is a passage in the Leon Vallas biography of Debussy, translated by Maire and Grace O’Brien and published in 1933:

“…Music hall types, like ‘Minstrels’ and ‘General Lavine, Eccentric’ – ‘the fellow was made of wood,’ Debussy used to say to indicate the mechanical stiffness required in the interpretation.”

Put these two together and you get the following, from Oscar Thompson’s Debussy biography of 1937:

“General Lavine, Eccentric. The general was made of wood and did duty as a vaudevillian at the Folies-Bergere. Even for a puppet he was absurdly stiff and ungainly, with a skip in his walk. After meeting various mishaps he concluded his ‘act’ with a surprising pirouette. Debussy indicated the mechanical rigidity required in characterizing his ‘eccentric’ by means of the keyboard. The ‘General’ is not humanized; his is a puppet grimace and a puppet limp, but something of the ironical attends his gait. Again, there is a suggestion of the American cake-walk.”

There the matter rests so far as the literature is concerned. Lockspeiser, Dumesnil and others who have written on Debussy do not touch on “General Lavine” at all, and an amusing little chapter of Debussyana has remained untold.

The source of Mr. Thompson’s trouble, by the way, is the French word “fantoche” in Cortot’s original text. This word does, to be sure, mean “puppet,” but is also very commonly employed in a figurative sense to describe a strange or fantastic human being; and it is obvious that Debussy’s phrase, “c’etait en bois, cet homme,” does not have to be taken literally.

Cortot commits a slight error in placing General La Vine at the Folies-Bergere, for he never played in that house. He made his first appearance in Paris at the Marigny Theatre on the Champ-Elysees in August, 1910, and he returned to that establishment two years later. He was back in Paris several times during the 1920’s, too, but that is not part of our story, for Debussy’s prelude appeared in 1913. But before discussing La Vine in Paris, it might be well to tell how he got there.

Edward La Vine was born in New York City in 1879. When he was a child his parents took him to Fort Wayne, Ind., to live, and at the age of 14 he went to work in an electrical factory there. He was not happy in Fort Wayne, and eventually ran away from home to wander around in the West States and in Mexico for several years. By 1902, he was back in New York helping to install electrical equipment on the Sixth Avenue Elevated, which up to that time had been a steam railroad.

He had always amused himself juggling the tools he used in the electric shops, and during the days when he was employed on the Sixth Avenue El he became convinced that he could juggle as well as or better than the professionals. He was tried out in a little uptown theater; he succeeded, and for the remaining eight years covered practically every corner of the country on the Orpheum circuit. By 1910 he was ready for the invasion of Europe.

The Marigny Theatre, where La Vine played after a tour of Italy, was an “American” house. Its very name indicates that – i.e., it was not called the Theatre Marigny. It featured American acts and printed its program partly in English – or what the management fondly thought was English – as well as in French. In other words the Marigny catered both to the American tourist trade and to the French delight in things American.

The bill at the Marigny in the summer of 1910 was divided into two parts – “La Revue de Marigny” and “Attractions.” The subject of this paper was one of the “attractions,” and was billed as “Great the American General La Vine, The man who has solidered (sic) all his life.” Other “attractions” were “Le Marabini, sculpteur sur glace,” “Jack _ , the World Champion of Diablo,” “Miss Heflein, American Singer,” and a baggy-pants comedian called Little Pich. The “Revue de Marigny” featured Mlle. Napierkowska, danseuse of the Opera-Comique. It was in eight scenes – “L’Avenue du Bois de Boulogne,” “Broadway la nuit,” “En Ecosse,” “La Cote d’Azur,” and “La Corne d’Or.” In “Broadway la nuit” La Napierkowska performed“la nouvelle creation de danse indienne.”

La Vine made a hit: this fact is attested by a significant bit of evidence among his memorabilia. He opened at the Marigny on August 1, 1910, and on August 5 he signed a contract to return there for the summer season of 1912. He could not come back earlier because he was under contract to play in Holland, Germany, Switzerland and England, and thereby hangs part of our tale.

La Vine’s success is further attested by his reception in the Paris press. The music halls were seldom reviewed in detail in those days; it was only the rare and exceptional act that received individual attention. On August 1 Le Figaro announces the Marigny program. It reviews it in the usual summary style on August 3. Then La Vine is mentioned in highly laudatory terms on the 9th and the 11th. On the 13th, the following appears:

“Where the devil does the redoubtable General Lavine get all his ideas? He is the hit of the show at the Marigny; the crowd turns out for him. And everything in his act is genuinely funny, including the animated scenery which, from time to time, brings new characters onto the stage, like the fisherman with his line whom Lavine, the pitiless general, forces to take a bath. There is nothing, down to the offstage noises, which does not serve to underline the comedy of this fantastic personage, juggling with his hat and his cigar. But such effects cannot be talked about. They must be seen. Quick, an aeroplane! Let’s go to the Marigny!”

La Vine is a tall man, and his “uniform” was calculated to make him look taller – one of the New York reviewers said he seemed to be at least nine feet high. The backdrop for his act, as he presented it in Paris, represented an army camp with little pyramidal tents drawn to an absurdly small scale. There were a cannon and canon balls, and a kind of free-standing scarecrow wearing a tuxedo coat and a top hat.

The General made his towering entrance in an incredibly elaborate costume. On his head he wore a three-cornered hat many sizes too small for him and apparently held on with a hairpin consisting of a huge nut-and-bolt arrangement which he unscrewed with a squeak during the act. His face was painted like a clown’s, but with the classic chin-whiskers of the stage tramp. He wore an immensely long swallow-tail coat covered with medals and chevrons; his epaulettes were either lighted buggy-lamps, as in the cartoon herewith, or little dinner table lamps, as in the photograph.

He wore rubber gloves, and during the act he removed them, inflated one, and milked it. Over his stomach he wore an immense thermometer. His huge clown’s shoes terminated in practicable pocket books; these opened and closed with a map, and from one of them he extracted a powder puff with which he dusted his red nose. His gun was made of rubber hose and wiggled as he carried it. His sword, which he suddenly extracted from its scabbard and brandished, was a long, thin saw. On his back he wore a hot water bottle for a knapsack.

La Vine began his act by fighting a battle with painted soldiers who were part of his animated scenery. (He made all of his own sets and props, drawing on his experience in the electrical business for the animated effects.) The fisherman was also painted on the flat; La Vine threw a rubber cannon ball at him, and when he disappeared into the sea over the horizon, a huge splash of rock salt was thrown up onto the stage, to the vast delight of the populace.

During the fight, La Vine removed the more cumbersome parts of his costume and, his victory won, proceeded to his juggling. The scarecrow suddenly and miraculously tossed him the classic three balls. When he was through juggling with these, he appropriated the scarecrow’s top hat and juggled with that and a lighted cigar. At the end of the act La Vine juggled with a cannon ball, a sledgehammer and a cigarette paper wadded into a little pellet. His offstage noises were the traditional rolls and booms of a drum.

All of this was much to the taste of the Paris public, and according to La Vine, the manager of the Marigny, whose name was Louis Borney, therefore conceived an idea worthy of Billy Rose. He planned to stage a new revue centered in the General, and he wanted to commission the best composers in Paris to write the music. Borney, says La Vine, approached Debussy to write the score for the General’s own part in this show, and consequently Debussy came to the Marigny repeatedly to see him. But the scheme fell through (incidentally, Debussy and La Vine never met). The new revue was never put together because La Vine was booked in other parts of Europe for two solid years, and could not get out of his contracts.

Darius Milhaud thinks it is quite possible that Debussy would have considered writing the music for a music hall revue, but he is doubtful about his accepting any proposal to contribute to a score in which the music of other composers was also used. Debussy was an aloof, aristocratic man and held a rather low opinion of most of his colleagues. Milhaud thinks the piano prelude simply embodies Debussy’s impression of Lavine’s act, but it is conceivable that it is a little more than that.

Debussy may have sketched some music for Borney’s new revue and then, when the project was canceled, turned the material left on his hands into the piece we now have. Hundreds of composers have done just that kind of thing. Debussy was fond of subtle little musical allusions, like the quotation of “God Save the King” in his “Hommage a S. Pickwick,” and the reference to “La Marseillaise” in “Feu d’artifice.” I have a notion that if “General Lavine” were simply an impression of the General’s performance it would contain some sly reference to the music he employed during his act, but it doesn’t. To be sure, you can prove practically anything you want by that kind of reasoning.

But whether it be an impression pure and simple or an impression concocted from music originally conceived as accompaniment to the General’s antics, the prelude certainly does convey an atmosphere of jerky movement and fantastic comedy. The little burlesque trumpet call of the opening, the preparatory bars “dans le style et le mouvement d’un cake-walk,” and above all the marking “spirituel et discret” at the point where the actual cake-walk begins, are Debussyan humor at its best.

I find the “puppet limp” hard to discover, but there are strong suggestions of jugglery all the way through, not the least of them being the abrupt chromatic passage in 16th notes first heard in the 29th and 30th bars. The title of the prelude, by the way, is in English, for very obvious reasons, but many pianists do not seem to realize this. One sees it often on concert programs with acute accents laboriously inserted over the e’s in “General,” although “eccentric” is scarcely a French word.

La Vine knows a lot about music and is well acquainted with many musicians. The entrance-music for his act was the once popular march called “The American Patrol,” while his juggling was accompanied by the “Chanson Indoue” from Rimsky-Korsakoff’s “Sadko,” popularly known today as “The Song of India.” It is rather surprising to find him using this piece in 1910 because it was little known in those days, but La Vine had picked it up in New York before he went to Paris, and later he took it with him all over the world. He claims credit for starting its vogue.

Another thing which La Vine started was the American career of Ethel Loginska. He met her in London, urged her to come to this country, and made arrangements for her to do so. And it was through one of La Vine’s musical friendships that this sketch came to be written. On the boat crossing to Europe in the summer of 1910 La Vine met the violinist, Antonio di Grassi, who later served for many years as a member of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. Di Grassi told the pianist, Carmen De Obarrio, about the General, and she told me.

During the first World War La Vine retired temporarily from the stage and went into the real estate business on Long Island. But he was always inventing little machines and gadgets, and at that time he patented a process for making “service bars” more quickly and cheaply than they had previously been manufactured. Recent events have caused him to revive this invention.

But for a long time between the wars he was back in vaudeville. A burlesque general was not quite the thing for a post-war world, and so for some years he did his act in a dress suit and opera cape, with new comic business. Later he adopted a sailor costume. He appeared all over Europe and America, Australia and South Africa in the 1920’s, but during that decade vaudeville was on the way out. The last review in the General’s clipping file is from the Minneapolis Journal of 1929.

He went to Los Angeles and was in the furniture and electrical business there for a number of years before moving to Twentynine Palms to take it easy. In addition to making service bars he is preparing to exploit some of his patents for household gimmicks of various kinds. But his most famous invention is one he concocted for Ringling Brothers years ago when that circus employed him to dream up clown acts. It is the automobile that first runs around the ring, then stalls and finally explodes into two parts, which go their separate ways. This deathless jest of the tin lizzy era will doubtless survive us all.

Images

Painters too were inordinately infatuated with the circus. Here Edward Degas' captures well the requisite daring of the circus acrobat taking flight night after night. The simple image of a person suspended in mid-air and defying the laws of gravity conveys the extraordinary power of the circus.

Edward Degas "Miss La-La at the Cirque Fernando" (1879)

Picasso was known to visit the circus night after night; here his portrayal of a family of circus performers tells us a great deal about their isolation and implicit despair.

Picasso, Famille de saltimbanques

Parade was a ballet composed by Satie in 1916-17 for the Ballets Russes. Its creators were an all-star cast: choreography by Massine, a plot-line by Cocteau, and costumes and sets by Picasso. The plot itself delighted in its own absurdity, for it consisted in circus performers attempting to draw in an audience which never materializes, no doubt reflecting on Parade's own possible fate as a spectacle. Picasso's curtain (see below) and sets definitely materialized, however-- note the Harlequin in the middle and the entire circus fantasy of winged horses, bareback riders, and animals towering over diminutive performers. Satie's music, with sirens and typewriters adding to the cacophony, did a good job of reflecting the three-ring circus mentality as well.

Curtain for Parade, 1917, Pablo Picasso

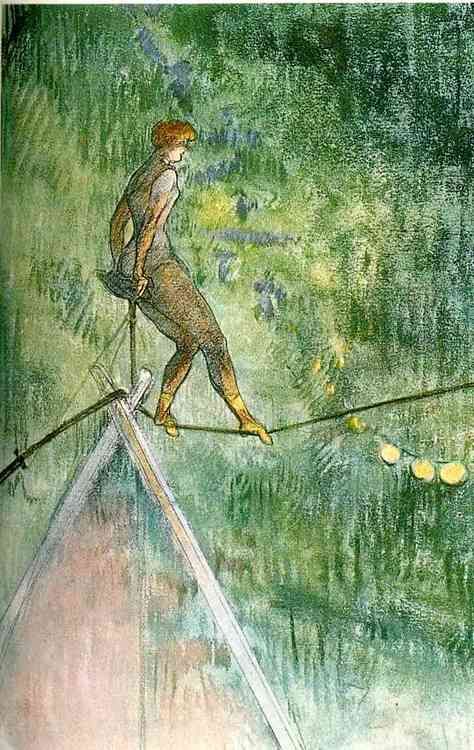

Painters continued to see circus performers as representing the risks and challenges in the life of an artist—the metaphorical tightrope walked by the outcast from normal life—and the following work by Debussy’s contemporary, Toulouse-Lautrec, provides a good example of that mindset.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), The Tightrope Walker (1896)

As this article from the Courrier Francais of June 2, 1901, says, clowns may amuse us well, but they risk breaking their necks in the process. A risky metier indeed!

Cindy Sherman (b. 1954), consummate masquerade artist, has made herself up as a clown for every occasion. Below, her masks bear witness still today to a central premise of the Commedia mindset: every human lives in multiple disguises. It is precisely those transformations and the ephemeral nature of reality that govern Debussy's art.

Cindy Sherman

Untitled #413, 2003

Chromogenic color print

44 1/4 x 29 3/8 inches

112.4 x 74.6 cm

(MP# CS--413)

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures

Cindy Sherman

Untitled #414, 2003

Chromogenic color print

57 3/16 x 38 3/16 inches

145.3 x 97 cm

(MP# CS—414)

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures

Musical examples

"General Lavine" - excentric, Prelude no. 6, Book 2, 1909-1910 (Kautsky, 2014)

(Note: this and other links to the Preludes require a free Spotify account)

The delightfully crass humor of this Prelude portrays Ed Lavine, the American-turned Parisian clown who was purported to play the piano with his toes. Small wonder that there should be a few "wrong notes." Debussy here eschews all the ambiguous emotions associated with circus life that were favored by his compatriots and happily opts instead for slapstick comedy. The opening series of rapid parallel triads is languidly revived in the middle section, where it soon morphs into a passing reference to "Camptown Races." We're left with a coded reminder of the cakewalk/minstrel style that was currently electrifying Paris.