Chapter I: Pierrot Conquers Paris

Section 1 - Poetry

Section 2 - Images

Section 3 - Music

Nineteenth century poets were infatuated with the Commedia dell'arte just as Debussy was, and here are some especially relevant examples of their poetry. Pierrot, with his sad face and infinitely malleable character, was a favorite.

Banville's "Pierrot" was used as a text by both Debussy and Poulenc.

Pierrot (1842)

by Theodore Banville (1823-1891)

Good old Pierrot, at whom the crowd gapes,

having concluded Harlequin's wedding,

walks along the Boulevard du Temple, lost in thought.

A girl in a supple garment

vainly teases him with a mischievous look;

And meanwhile, mysterious and smooth,

taking her sweetest delight in him,

the white moon, bull-horned,

throws a furtive glance

at her friend Jean Gaspard Deburau.

Le bon Pierrot, que la foule contemple,

Ayant fini les noces d'Arlequin,

Suit en songeant le boulevard du Temple.

Une fillette au souple casaquin

En vain l'agace de son oeil coquin;

Et cependant mystérieuse et lisse

Faisant de lui sa plus chère délice,

La blanche lune aux cornes de taureau

Jette un regard de son oeil en coulisse

À son ami Jean Gaspard Deburau.

English translation © 2006 by Bertram Kottmann, reprinted with permission.

LaForgue (1860-1887) wrote poem after poem about Pierrot. For this influential French poet, the sad clown encompassed every possible madness and gave rise to poetry which glories in the absurd.

Pierrots I (1886)

By Jules Laforgue (1860-1887)

Emerges, on a taut neck,

From a starched ruff idem

A beardless face, cold-creamed,

A beanpole: hydrocephalic.

The eyes are drowned in opium

In universal license

The clownish mouth bewitched

A singular geranium.

A mouth, now bottomless pit

Glacially screeching laughter,

Now a transcendental opening,

Vain smile of La Gioconda.

Planting their floury cones

On a black silk cut-throat's scarf,

They'll make their crow's-feet laugh

And wrinkle their trefoil noses.

For gem-stoned rings, on hand,

They've Egyptian scarabs,

In well-cut buttonholes,

Dandelions from the wasteland.

They go, eating the azure,

Sometimes vegetables too,

Hard-boiled eggs, and mandarins,

And rice as white as their costume.

They're of the Pallid sect,

They've nothing to do with God at all.

And whistle: "All's for the best

In this best of Carnivals!"

C'est, sur un cou qui, raide, émerge

D'une fraise empesée idem,

Une face imberbe au cold-cream,

Un air d'hydrocéphale asperge.

Les yeux sont noyés de l'opium

De l'indulgence universelle,

La bouche clownesque ensorcèle

Comme un singulier géranium.

Bouche qui va du trou sans bonde

Glacialement désopilé,

Au transcendental en-allé

Du souris vain de la Joconde.

Campant leur cône enfariné

Sur le noir serre-tête en soie,

Ils font rire leur patte d'oie

Et froncent en trèfle leur nez.

Ils ont comme chaton de bague

Le scarabée égyptien,

À leur boutonnière fait bien

Le pissenlit des terrains vagues.

Ils vont, se sustentant d'azur!

Et parfois aussi de légumes,

De riz plus blanc que leur costume,

De mandarines et d'oeufs durs.

Ils sont de la secte du Blême,

Ils n'ont rien à voir avec Dieu,

Et sifflent: "Tout est pour le mieux,

"Dans la meilleur' des mi-carême!"

English translation © 2007 by A. S. Kline, reprinted with permission.

And here, find the text to the entire Pierrot Lunaire, made famous in Arnold Schoenberg's revolutionary sprechstimme setting. Written first in French, the poems reflect well the mad Pierrot who also inhabited Debussy's imagination, though Debussy imagined him as a far gentler chap.

Pierrot Lunaire

by Otto Erich Hartleben (1864-1905)

After the original French by Albert Giraud (1860-1929)

Moondrunk

The wine we drink through the eyes

The moon pours down at night in waves,

And a flood tide overflows

The silent horizon.

Longings beyond number, gruesome sweet frissons,

Swim through the flood.

The wine we drink through the eyes

The moon pours down at night in waves.

The poet, slave to devotion,

Drunk on the sacred liquor,

Enraptured, turns his face to Heaven

And staggering sucks and slurps

The wine we drink through the eyes.

1. Mondestrunken

Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt,

Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder,

Und eine Springflut überschwemmt

Den stillen Horizont.

Gelüste schauerlich und süß,

Durchschwimmen ohne Zahl die Fluten!

Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt,

Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder.

Der Dichter, den die Andacht treibt,

Berauscht sich an dem heilgen Tranke,

Gen Himmel wendet er verzückt

Das Haupt und taumelnd saugt und schlürft er

Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt.

Columbine

The moonlight's pale blossoms,

The white wonder-roses,

Bloom in July nights.

O could I pluck but one!

To soothe my deepest sorrow,

Through darkening streams I seek

The moonlight's pale blossoms,

The white wonder-roses.

All my longings would be satisfied,

Dared I as gently

As a fairy sprite to scatter

Over your brown tresses

The moonlight's pale blossoms.

2. Columbine

Des Mondlichts bleiche Blüten,

Die weißen Wunderrosen,

Blühn in den Julinachten -

O brach ich eine nur!

Mein banges Leid zu lindern,

Such ich am dunklen Strome

Des Mondlichts bleiche Blüten,

Die weißen Wunderrosen.

Gestillt wär all mein Sehnen,

Dürft ich so märchenheimlich,

So selig leis - entblättern

Auf deine brauenen Haare

Des Mondlichts bleiche Blüten!

The dandy

With a ghostly light ray

The moon illumines the crystal flasks

Upon the dark altar - the holy Washbasin

Of the taciturn Dandy from Bergamo.

In the resonant bronze basin

The fountains laugh a metallic clangor.

With a ghostly light ray

The moon illumines the crystal flasks.

Pierrot with waxen complexion

Stands deep in thought: What makeup for today?

He shoves aside the red and oriental green

And paints his face in sublime style

With a ghostly light ray.

3. Der Dandy

Mit einem phantastischen Lichtstrahl

Erleuchtet der Mond die krystallnen Flacons

Auf dem schwarzen, hochheiligen Waschtisch

Des schweigenden Dandys von Bergamo.

In tönender, bronzener Schale

Lacht hell die Fontaine, metallischen Klangs.

Mit einem phantastischen Lichtstrahl

Erleuchtet der Mond die krystallnen Flacons.

Pierrot mit dem wächsernen Antlitz

Steht sinnend und denkt: wie er heute sich schminkt?

Fort schiebt er das Rot und das Orients Grün

Und bemalt sein Gesicht in erhabenem Stil

Mit einem phantastischen Mondstrahl.

A pale washerwoman

A pale washerwoman

Washes faded garments at nighttime.

Naked, silver-white arms

She stretches down into the flood.

Breezes tiptoe through the clearing,

Lightly ruffle the stream.

A pale washerwoman

Washes faded garments at nighttime.

And the gentle maid of heaven,

Softly fondled by the boughs,

Spreads her linen spun from moonbeams

Across the dusky meadows -

A pale washerwoman.

4. Eine blasse Wäscherin

Eine blasse Wäscherin

Wäscht zur Nachtzeit bleiche Tücher;

Nackte, silberweiße Arme

Streckt sie nieder in die Flut.

Durch die Lichtung schleichen Winde,

Leis bewegen sie den Strom.

Eine blasse Wäscherin

Wäscht zur Nachtzeit bleiche Tücher.

Und die sanfte Magd des Himmels,

Von den Zweigen zart umschmeichelt,

Breitet auf die dunklen Wiesen

ihre lichtgewobnen Linnen -

Eine blasse Wäscherin.

Chopin Waltz

As a bleached drop of blood

Stains a sufferer's lips,

So lurks within this music

The lure of annihilation.

In untamed strains the chords disorder

Despair's icy dream -

As a bleached drop of blood

Stains a sufferer's lips.

Fierce, exulting, sweet, and yearning,

Melancholy dismal waltzes,

You cling to my consciousness,

You are borne on my thoughts

Like a bleached drop of blood.

5. Valse de Chopin

Wie ein blasser Tropfen Bluts

Färbt die Lippen einer Kranken,

Also ruht auf diesen Tönen

Ein vernichtungssüchtger Reiz.

Wilder Lust Accorde [stören]1

Der Verzweiflung eisgen Traum -

Wie ein blasser Tropfen Bluts

Färbt die Lippen einer Kranken.

Heiß und jauchzend, süß und schmachtend,

Melancholisch düstrer Walzer,

Kommst mir nimmer aus den Sinnen!

Haftest mir an den Gedanken,

Wie ein blasser Tropfen Bluts!

Madonna

Ascend, O Mother of All Sorrows

The altar of my verses!

The sword's fury has drawn blood

From thy withered breasts.

Thy eternal open wounds

Are like eyes, red and open.

Ascend, O Mother of All Sorrows

The altar of my verses!

In thy shriveled hands

Thou holdest thy Son's body,

Revealed to all mankind -

But mankind's gaze is turned away

From thee, O Mother of All Sorrows.

6. Madonna

Steig, o Mutter aller Schmerzen,

Auf den Altar meiner Verse!

Blut aus deinen magren Brusten

Hat des Schwertes Wut vergossen.

Deine ewig frischen Wunden

Gleichen Augen, rot und offen.

Steig, o Mutter aller Schmerzen,

Auf den Altar meiner Verse!

In den abgezehrten Händen

Hältst du deines Sohnes Leiche.

Ihn zu zeigen aller Menschheit -

Doch der Blick der Menschen meidet

Dich, o Mutter aller Schmerzen!

The sick moon

You dark moon, deathly ill,

Laid over heaven's sable pillow,

Your fever-swollen gaze

Enchants me like alien melody.

You die of insatiable pangs of love,

Suffocated in longing,

You dark moon, deathly ill,

Laid over heaven's sable pillow.

The hotblooded lover

Slinking heedless to the tryst

You hearten with your play of light,

Your pale blood wrung from torment,

You dark moon, deathly ill.

7. Der kranke Mond

Du nächtig todeskranker Mond

Dort auf des Himmels schwarzem Pfühl,

Dein Blick, so fiebernd übergroß,

Bannt mich wie fremde Melodie.

An unstillbarem Liebesleid

Stirbst du, an Sehnsucht, tief erstickt,

Du nächtig todeskranker Mond

Dort auf des Himmels schwarzem Pfühl.

Den Liebsten, der im Sinnenrausch

Gedankenlos zur Liebsten schleicht,

Belustigt deiner Strahlen Spiel -

Dein bleiches, qualgebornes Blut,

Du nächtig todeskranker Mond.

Night

Giant black butterflies

Have blotted out the sunshine.

A closed book of magic spells,

The horizon sleeps - silent.

Vapors from lost abysses

Breathe out an odor, murdering memory.

Giant black butterflies

Have blotted out the sunshine.

And from Heaven earthward

Gliding down on leaden wings

The invisible monsters

Descend upon our human hearts...

Giant black butterflies.

8. Nacht (Passacaglia)

Finstre, schwarze Riesenfalter

Töteten der Sonne Glanz.

Ein geschlossnes Zauberbuch,

Ruht der Horizont - verschwiegen.

Aus dem Qualm verlorner Tiefen

Steigt ein Duft, Erinnrung mordend!

Finstre, schwarze Reisenfalter

Töteten der Sonne Glanz.

Und vom Himmel erdenwärts

Senken sich mit schweren Schwingen

Unsichtbar die Ungetume

Auf die Menschenherzen nieder...

Finstre, schwarze Riesenfalter.

Prayer to Pierrot

Pierrot! My laughter

I've unlearned.

The image of splendor

Melted away.

To me the flag waves black

Now from the mast.

Pierrot! My laughter

I've unlearned.

O give me back -

Horse-doctor to the soul,

Snowman of Lyric,

Your Lunar Highness,

Pierrot! my laughter.

9. Gebet an Pierrot

Pierrot! Mein Lachen

Hab ich verlernt!

Das Bild des Glanzes

Zerfloß - Zerfloß!

Schwarz weht die Flagge

Mir nun vom Mast.

Pierrot! Mein Lachen

Hab ich verlernt!

O gieb mir wieder,

Roßarzt der Seele,

Schneemann der Lyrik,

Durchlaucht vom Monde,

Pierrot - mein Lachen!

Theft

Princely red rubies,

Bloody drops of ancient glory,

Slumber in the coffins,

Down there in the sepulchers.

Nighttimes, with his drinking buddies,

Pierrot climbs down - to steal

Princely red rubies,

Bloody drops of ancient glory.

But look-their hair stands on end,

Fear roots them to the spot:

Through the darkness - like eyes! -

Out of the coffins stare

Princely red rubies.

10. Raub

Rote, fürstliche Rubine,

Blutge Tropfen alten Ruhmes,

Schlummern in den Totenschreinen,

Drunten in den Grabgewolben.

Nachts, mit seinen Zechkumpanen,

Steigt Pierrot hinab - zu rauben

Rote, fürstliche Rubine,

Blutge Tropfen alten Ruhmes.

Doch da - strauben sich die Haare,

Bleiche Furcht bannt sie am Platze:

Durch die Finsternis - wie Augen! -

Stieren aus den Totenschreinen

Rote, fürstliche Rubine.

Red mass

At the gruesome Eucharist,

In golden glitter,

In flickering candlelight,

To the altar comes - Pierrot!

His hand, consecrated to God,

Tears open the priestly robes

At the gruesome Eucharist,

In golden glitter.

Signing the cross,

He shows the suffering souls

The dripping red Host:

His heart - in bloody fingers -

At the gruesome Eucharist.

11. Rote Messe

Zu grausem Abendmahle,

Beim Blendeglanz des Goldes,

Beim Flackerschein der Kerzen,

Naht dem Altar - Pierrot!

Die Hand, die gottgeweihte,

Zerreißt die Priesterkleider

Zu grausem Abendmahle,

Beim Blendeglanz des Goldes

Mit segnender Geberde

Zeigt er den bangen Seelen

Die triefend rote Hostie:

Sein Herz - in blutgen Fingern -

Zu grausem Abendmahle!

Gallows song

The scrawny wench

With the long neck

Will be

His last lover.

Stuck in his brain

Like a nail is

The scrawny wench

With the long neck.

Thin as a pine tree,

Pigtail down her neck-

Lasciviously she'll

Embrace the knave,

The scrawny wench!

12. Galgenlied

Die dürre Dirne

Mit langem Halse

Wird seine letzte

Geliebte sein.

In seinem Hirne

Steckt wie ein Nagel

Die dürre Dirne

Mit langem Halse.

Schlank wie die Pinie,

Am Hals ein Zöpfchen -

Wollüstig wird sie

Den Schelm umhalsen,

Die dürre Dirne!

Beheading

The moon, a shining scimitar

On a black silk cushion,

Preternaturally large - glowers down

Through night's pall of sorrow.

Pierrot wanders about restlessly

And stares aloft in deadly fear

At the moon, a shining scimitar

On a black silk cushion.

His knees tremble,

He collapses senseless.

He fancies it's already whistling down

In vengeance on his guilty neck,

The moon, the shining scimitar.

13. Enthauptung

Der Mond, ein blankes Türkenschwert

Auf einem schwarzen Seidenkissen,

Gespenstisch groß - dräut er hinab

Durch schmerzendunkle Nacht.

Pierrot irrt ohne Rast umher

Und starrt empor in Todesängsten

Zum Mond, dem blanken Türkenschwert

Auf einem schwarzen Seidenkissen.

Es schlottern unter ihm die Knie,

Ohnmächtig bricht er jäh zusammen.

Er wähnt: es sause strafend schon

Auf seinen Sünderhals hernieder

Der Mond, das blanke Türkenschwert.

Crosses

Poems are poets' holy crosses

On which they bleed in silence,

Struck blind by phantom swarms

Of fluttering vultures.

Swords have feasted on their bodies,

Reveling in the scarlet blood!

Poems are poets' holy crosses

On which they bleed in silence.

Dead the head, the tresses stiffened,

Far away the noisy rabble.

Slowly the sun sinks,

A red royal crown. -

Poems are poets' holy crosses.

14. Die Kreuze

Heilge Kreuze sind die Verse,

Dran die Dichter stumm verbluten,

Blindgeschlagen von der Geier

Flatterndem Gespensterschwarme!

In den Leibern schwelgten Schwerter,

Prunkend in des Blutes Scharlach!

Heilge Kreuze sind die Verse,

Dran die Dichter stumm verbluten.

Tot das Haupt - erstarrt die Locken -

Fern, verweht der Lärm des Pöbels.

Langsam sinkt die Sonne nieder,

Eine rote Königskrone. -

Heilge Kreuze sind die Verse!

|

15. Heimweh |

Homesickness |

|

Lieblich klagend - ein krystallnes Seufzen

Und es tönt durch seines Herzens Wüste,

Da vergißt Pierrot die Trauermienen! |

Sweetly lamenting - a crystalline sigh

And it sounds through his heart's wasteland,

Then Pierrot forgets the mask of tragedy! |

Practical joke

Into the gleaming pate of Cassander,

Who's crying bloody murder,

Pierrot drills with a disingenuous air,

Gently, with a trepan [skull-borer]!

Then tamps in with his finger

His genuine Turkish tobacco

Into the gleaming pate of Cassander,

Who's crying bloody murder.

Then screws a cherry pipestem

Into the bald spot behind

And smugly puffs away on

His genuine Turkish tobacco

From the gleaming pate of Cassander.

16. Gemeinheit!

In den blanken Kopf Cassanders,

Dessen Schrein die Luft durchzetert,

Bohrt Pierrot mit Heuchlermienen,

Zärtlich - einen Schädelbohrer!

Darauf stopft er mit dem Daumen

Seinen echten türkischen Taback

In den blanken Kopf Cassanders,

Dessen Schrein die Luft durchzetert!

Dann dreht er ein Rohr von Weichsel

Hinten in die glatte Glatze

Und behäbig schmaucht und pafft er

Seinen echten türkischen Taback

Aus dem blanken Kopf Cassanders!

Parody

Knitting needles gleaming and flashing

In her gray hair,

The duenna sits there muttering

In her little red dress.

She's waiting in the arbor;

She loves Pierrot to distraction,

Knitting needles gleaming and flashing

In her gray hair.

Of a sudden-hark!-a whisper!

A breath of wind softly snickers:

The moon, wicked aping scoffer,

Beams down a simulacrum of

Knitting needles gleaming and flashing.

17. Parodie

Stricknadeln, blank und blinkend,

In ihrem grauen Haar,

Sitzt die Duenna murmelnd,

Im roten Röckchen da.

Sie wartet in der Laube,

Sie liebt Pierrot mit Schmerzen,

Stricknadeln, blank und blinkend,

In ihrem grauen Haar.

Da plötzlich - horch! - ein Wispern!

Ein Windhauch kichert leise:

Der Mond, der böse Spötter,

Äfft nach mit seinen Strahlen -

Stricknadeln, blink und blank.

Moonfleck

A white fleck of bright moon

On the back of his black coat,

Pierrot sets off one balmy evening,

To seek his fortune.

Suddenly something's awry in his toilette;

He casts about until he finds it-

A white fleck of bright moon

On the back of his black coat.

Drat! he thinks: a fleck of plaster!

Wipes and wipes, but-can't get it off!

So on he goes, his pleasure poisoned,

Till break of day, rubbing and rubbing

A white fleck of bright moon.

18. Der Mondfleck

Einen weißen Fleck des hellen Mondes

Auf dem Rücken seines schwarzen Rockes,

So spaziert Pierrot im lauen Abend,

Aufzusuchen Glück und Abenteuer.

Plötzlich - stört ihn was an seinem Anzug,

Er beschaut sich rings und findet richtig -

Einen weißen Fleck des hellen Mondes

Auf dem Rücken seines schwarzen Rockes.

Warte! denkt er: das ist so ein Gipsfleck!

Wischt und wischt, doch - bringt ihn nicht herunter!

Und so geht er, giftgeschwollen, weiter,

Reibt und reibt bis an den frühen Morgen --

Einen weißen Fleck des hellen Mondes.

Serenade

With a grotesquely outsized bow

Pierrot scrapes on his viola.

Like a stork on one leg,

He plucks a doleful pizzicato.

Suddenly here's Cassander - raging

At the nighttime virtuoso -

With a grotesquely outsized bow

Pierrot scrapes on his viola.

He tosses the viola aside,

With his left hand delicately

Takes Sir Baldy by the collar -

Dreamily he plays on his pate

With a grotesquely outsized bow.

19. Serenade

Mit groteskem Riesenbogen

Kratzt Pierrot auf seiner Bratsche,

Wie der Storch auf einem Beine,

Knipst er trüb ein Pizzicato.

Plötzlich naht Cassander - wütend

Ob des nächtgen Virtuosen -

Mit groteskem Riesenbogen

Kratzt Pierrot auf seiner Bratsche.

Von sich wirft er jetzt die Bratsche:

Mit der delikaten Linken

Faßt den Kahlkopf er am Kragen -

Träumend spielt er auf der Glatze

Mit groteskem Riesenbogen.

Homeward journey

Moonbeam is the rudder,

Waterlily serves as boat:

Thus Pierrot fares southward

On a fair following wind.

The stream hums deep scales

And rocks the fragile craft.

Moonbeam is the rudder,

Waterlily serves as boat.

To Bergamo, to Homeland,

Pierrot now wends his way;

Faintly in the east

Glows the green horizon.

- Moonbeam is the rudder.

20. Heimfahrt (Barcarole)

Der Mondstrahl ist das Ruder,

Seerose dient als Boot;

Drauf fährt Pierrot gen Süden

Mit gutem Reisewind.

Der Strom summt tiefe Skalen

Und wiegt den leichten Kahn.

Der Mondstrahl ist das Ruder,

Seerose dient als Boot.

Nach Bergamo, zur Heimat,

Kehrt nun Pierrot zurück;

Schwach dämmert schon im Osten

Der grüne Horizont.

- Der Mondstrahl ist das Ruder.

O sweet fragrance

O redolence from fairytale times,

Bewitch again my senses!

A knavish swarm of silly pranks

Buzzes down the gentle breeze.

A happy impulse calls me back

To joys I have long neglected:

O redolence from fairytale times,

Bewitch me again!

All my ill humors I've renounced;

From my sun-framed window

I behold untrammeled the beloved world

And dream me out to blissful vistas...

O redolence from fairytale times.

21. O alter Duft

O alter Duft aus Märchenzeit,

Berauschest wieder meine Sinne;

Ein närrisch Heer von Schelmerein

Durchschwirrt die leichte Luft.

Ein glückhaft Wünschen macht mich froh

Nach Freuden, die ich lang verachtet:

O alter Duft aus Märchenzeit,

Berauschest wieder mich!

All meinen Unmut gab ich preis;

Aus meinem sonnumrahmten Fenster

Beschau ich frei die liebe Welt

Und träum hinaus in selge Weiten...

O alter Duft - aus Märchenzeit!

English translation © by Mimmi Fulmer and Ric Merritt, reprinted with permission.

Un mot au soleil pour commencer

(A Word to the Sun for Starters)

By Jules Laforgue

|

Soleil ! soudard plaqué d'ordres et de crachats, Sache que les Pierrots, phalènes des dolmens Et qu'ils gardent pour toi des mépris spéciaux, Continue à fournir de couchants avinés Va, Phoebus! Mais, Dèva, dieu des réveils cabrés, Certes, tu as encor devant toi de beaux jours; Pour aujourd'hui, vieux beau, nous nous contenterons — Sache qu'on va disant d'une belle phrase, os Ô vision du temps où l'être trop puni, |

Mercenary Sun, beknighted, gob-gonged, passed up high, Know that the Pierrots, too, the moths of megaliths, Know that they hold for you a special scorn of theirs, You carry on supplying settings — bibulous, Go, Phoebal! But, Deva, god of reared arising, Yes, true, you've still some splendid days to come, above, And so, old Beau, today we'll be content for now — So know that there's a fine phrase going round; it's bone Oh, vision of time when, lashed too often, being flings |

English translation © Peter Dale, Poems of Jules Laforgue. London: Anvil Press Poetry, 2001.

Complainte de la lune en province

(Complaint of the Moon in the Provinces)

By Jules Laforgue

Ah, moon the fine, full Moon,

Large as a fortune calls the tune!

Far off the sounds of last post die.

Someone, deputy mayor, walks by;

Harpsichord, opposite, plays an air;

A cat is coming across the square:

The province sleeping like a board!

Thumping out a final chord,

The piano shuts its window tight.

What exactly is the time of night?

Calm moon, this exile's hell to me.

But must one say: so let it be?

Moon, Moon, you dilettante, you,

Common to all climates; your view

Was the Missouri yesterday;

The Paris ramparts came your way,

The blue Norwegian fjords, snow

Of poles, seas — and what I don't know.

Oh happy Moon, thus you perceive,

This very moment, her train leave,

Her honeymoon she's going on.

To Scotland, that's where they have gone.

Some trap this winter if she'd read

My verse as meaning what it said I

Moon, vagabond moon, shall we make

A common cause, one manner take?

Nights, oh rich. I'm a dead duck,

The province in my heart stuck!

And the moon has, the good old dear,

Cotton wool stuffed in each ear.

Ah ! La belle pleine Lune,

Grosse comme une fortune !

La retraite sonne au loin,

Un passant, monsieur l'adjoint ;

Un clavecin joue en face,

Un chat traverse la place :

La province qui s'endort !

Plaquant un dernier accord,

Le piano clôt sa fenêtre.

Quelle heure peut-il bien être ?

Calme lune, quel exil !

Faut-il dire : ainsi soit-il ?

Lune, ô dilettante lune,

A tous les climats commune,

Tu vis hier le Missouri,

Et les remparts de Paris,

Les fiords bleus de la Norwège,

Les pôles, les mers, que sais-je ?

Lune heureuse ! Ainsi tu vois,

A cette heure, le convoi

De son voyage de noce !

Ils sont partis pour l'Écosse.

Quel panneau, si, cet hiver,

Elle eût pris au mot mes vers !

Lune, vagabonde lune,

Faisons cause et mœurs communes ?

Ô riches nuits ! Je me meurs,

La province dans le cœur !

Et la lune a, bonne vieille,

Du coton dans les oreilles.

English translation © Peter Dale, Poems of Jules Laforgue. London: Anvil Press Poetry, 2001.

Complainte de l'époux outragé (Complaint of the outraged husband)

By Jules Laforgue

Based on the popular song:

'What did you do at the fountain?'

'Why at the church of the Magdalen,

Damn odd, my darling dove.

Why at the church of the Magdalen?'

'Went there to pray for a son again,

My God, my only love;

Went there to pray for a son again.'

'You stood in a corner and never went thence,

Damn odd, my darling dove!

You stood in a corner and never went thence.'

'No chair's a saving of several pence,

My God, my only friend;

No chair's a saving of several pence.'

'Officer's figure caught my eyes,

Damn odd, my darling dove!

Officer's figure caught my eyes.'

'That was some Christ you saw life-size,

My God, my only love;

That was some Christ you saw life-size.'

'Legion of Honour Christs don't wear,

Damn odd, my darling dove!

Legion of Honour Christs don't wear.'

'That was Calvary's heart-wound, bare,

My God, my only love;

That was Calvary's heart-wound, bare.'

'Only the sides of Christs are lanced,

Damn odd, my darling dove!

Only the sides of Christ are lanced.'

'That was a splash of blood that chanced,

My God, my only love;

That was a splash of blood that chanced.'

'In Holy Week none speaks of such,

Damn odd, my darling dove!

In Holy Week none speaks of such!'

'That was a love I felt too much,

My God, my only love,

That was a love I felt too much:

'And I, in your head'll blast a hole,

Damn odd, my darling dove,

And I, in your head'll blast a hole!'

'Then he will have my immortal soul,

My God, my only love,

Then he will have my immortal soul!'

Sur l’air Populaire:

« Qu’allais-tu faire à la fontaine ? »

- Qu'alliez-vous faire à la Mad'leine,

Corbleu, ma moitié.

Qu'alliez-vous faire à la Mad'leine ?

- J'allais prier pour qu'un fils nous vienne,

Mon Dieu, mon ami;

J'allais prier pour qu'un fils nous vienne.

- Vous vous teniez dans un coin, debout,

Corbleu, ma moitié!

Vous vous teniez dans un coin debout.

- Pas d'chaise économis' trois sous,

Mon Dieu, mon ami;

Pas d'chaise économis' trois sous.

- D'un officier, j'ai vu la tournure,

Corbleu, ma moitié!

D'un officier, j'ai vu la tournure.

- C'était ce Christ grandeur nature,

Mon Dieu, mon ami;

c'était ce Christ grandeur nature.

- Les Christs n'ont pas la croix d'honneur,

Corbleu, ma moitié!

Les Christs n'ont pas la croix d'honneur.

- C'était la plaie du Calvaire, au cœur,

Mon Dieu, mon ami;

C'était la plaie du Calvaire au cœur.

- Les Christs n'ont qu'au flanc seul la plaie,

Corbleu, ma moitié!

Les Christs n'ont qu'au flanc seul la plaie!

- C’était une goutte envolée,

Mon Dieu, mon ami;

C'était une goutte envolée.

- Aux Crucifix on n' parl' jamais,

Corbleu, ma moitié!

Aux Crucifix on n' parl' jamais!

- C'était du trop d'amour qu'j'avais,

Mon Dieu, mon ami,

C'était du trop d'amour qu'j'avais!

- Et moi j'te brûl'rai la cervelle,

Corbleu, ma moitié,

Et moi j'te brûl'rai la cervelle!

- Lui, il aura mon âme immortelle,

Mon Dieu, mon ami,

Lui, il aura mon âme immortelle!

English translation © Peter Dale, Poems of Jules Laforgue. London: Anvil Press Poetry, 2001.

Images

The Belgian painter, James Ensor, makes the macabre links between Pierrot and death all too clear in this and other paintings. The thin line between comedy and tragedy is unmistakable, and Ensor's fascination with masks here spreads from the Commedia to the skeletons which decked his art studio.

Image source: Frans Vandewalle (CC BY-NC 2.0)

See here Paris's most famous Pierrot, Charles Duburau, who starred at the Theâtre de Funambules and was immortalized in the film, Children of Paradise.

Pierrot Laughing, 1855 Photograph of Charles Duburau, Nadar (1820-

1910)

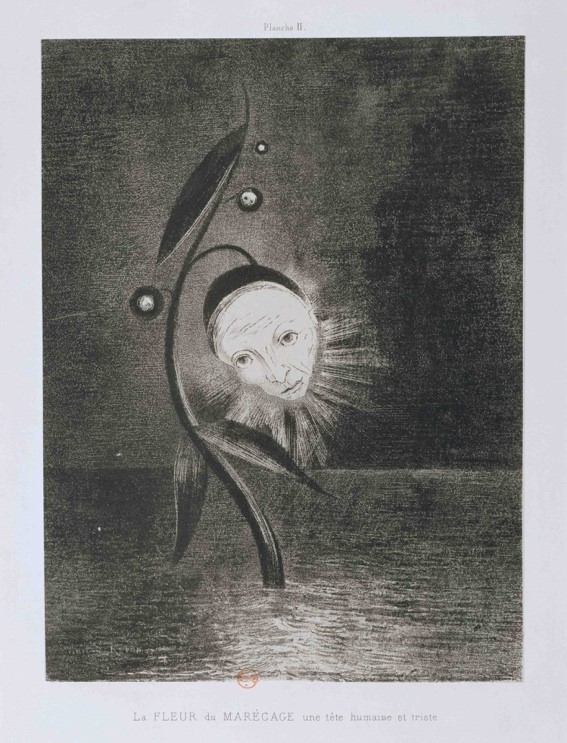

And here, the take of one of Debussy's favorite artists, Redon, on the sad--and here, decaptiated--clown.

The Marsh Flower, A Sad and Human Head, 1885, Odilon Redon (1840-1916)

Picasso was fascinated with the Commedia, transforming himself into Harlequin into a number of paintings and inserting Pierrot and Harlequin into many others.

Pierrot, 1918, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

And here another French painter gets entangled with the Commedia. Who would have guessed that this painter, so famous for his elongated women, would portray himself as Pierrot?

Self-Portrait as Pierrot, 1915, Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920)

Maurice Sand, son of George Sand, Chopin's lover, wrote a massive book on the Commedia dell'arte, complete with detailed illustrations. Below is one example.

Illustration of Harlequin by Maurice Sand.

Harlequin made his way into popular media as well, adorning many a journal cover and feature story.

Musical examples

Suite Bergamasque, 1890-1905 (Walter Gieseking, 1956)

Given that the Commedia was said to originate in Bergamo, and Pierrot was indelibly associated with the moon, Suite Bergamasque's "Clair de Lune" is certainly a first step in comprehending Debussy's relationship to the Commedia.

Masques, 1904 (Gieseking, 1953)

Masques was early on conceived as part of a second Suite Bergamasque, and its title, "Masks," makes clear the link to the Commedia's artfully masked characters.

The Etudes have no titular connection to the Commedia, but of all Debussy's works they are the most volatile, the most unpredictable, the most capricious. Their link with the mindset of the Commedia is undeniable.

Further Notes on The Etudes:

No. 1, Pour les cinq doigts d’après Monsieur Czerny is the most obvious comedic take-off of the lot, for it is, of course, a wicked parody of Czerny exercises. However, its fascination lies in the fact that its prosaic five finger patterns manage, against all odds, to flirt with loveliness, and in fact to frequently become outright beautiful. The music seems to insist that parody and authenticity can exist on the same turf, that the coexistence of opposites is the way of the world. The annoying task of the sullen child and the arabesques of the elevated artist cannot be so easily unraveled from one another, and here one of them constantly interrupts and transforms the other. Eventually Czerny’s opening scales become a form of color rather than a piece of drudgery(e.g. m. 72) and they’re then so pleased with themselves that they multiply in celebration, swirling to a grand finale that traverses the entire keyboard in one last rapid-fire scale.

No. 2, Pour les tierces is perhaps the least commedic of the set. Debussy seems more influenced here by Chopin’s etude in thirds than by Pierrot. One thing follows another in rational order and virtuosity reigns, but even here there are scherzando moments that come upon us unexpectedly and remind us that a circus is always lurking around the corner. Measure 6 is the first example, with its tenor melody in staccato emerging suddenly in the midst of such well-oiled legato. Then comes the unprepared intensity of the cry at m. 13, which recurs at the end. As in the other etudes, Debussy calls for rubato here, using the rubato as a way to subvert the predictability of a steady meter. The big difference here is that the outlying moments feel more integrated than ostracized; tempo, dynamic, and articulation are more of a piece in this etude, and distraction is pushed aside rather than encouraged.

No. 3, Pour les quartes, delights in the unfamiliarity of quartal harmonies, and the shock of non-sequitors, where one kind of material follows on the heels of another without preparation. The violence of the explosive stretto in m. 7 has nothing to do with the dance-world dolce of the opening, and even the musical terminology used in this Etude is elusive. Where else in the literature does one encounter instructions like “ballabile” and “scherzare?” A new vocabulary was needed to instruct the performer when melodies were fragmentary, rhythms constantly shifting, and rough and frightening fortes prone to burst out in the midst of bucolic tranquility.

No. 4, Pour les sixtes, with its gently undulating, sinuous opening, deceives us into thinking that at last an Etude will stay true to its opening promise. After all, these pieces are so brief they surely do not necessitate contrast. But no. The dolce opening mood again proves brittle, and its calm contemplations are shattered by a nervous repeated note figure (m. 21) that, though temporarily banished by a dancing rubato idea, reasserts its jittery presence (m. 38), and only gradually gives way to the sensuality of the opening at the very end. Debussy wrote while composing the piece that “For a longtime the continuous use of sixths remind me of pretentious young ladies sitting in a salon, sulkily doing their tapestry work and envying the scandalous laughter of the naughty ninths... “

No. 5, Pour les octaves, does what all octave etudes are supposed to do – it raises hell. But this one not only makes difficulties for the performer, but also for the listener. It would be the rare listener indeed who could accurately follow the meter and conduct this piece. What begins as a recognizable, if unusually boisterous, waltz, quickly sheds that identity, transforming itself eventually into a would-be marimba lick, “très égalment rythmé,” “con sordino” and obviously sans nuance. One can virtually hear drumsticks clicking. That doesn’t last either, though, as the single notes of the marimba multiply into parallel octaves with manically difficult leaps. (m. 76) These subside just as rapidly as the material that follows—the etudes exist in a highly ephemeral universe where change is the only constant. Eventually the opening returns and the piece crashes to an end with a loud, affirmative, and tonal cadence – the acrobat here has earned his applause, but certainly not by dint of any known routine!

No. 6, Pour les huit doigts, forms a nice counterpart to “Pour le cinq doigts.” Here the pianist has lost one finger on each hand, condemned to play without a thumb, but whizzing along all the same. This etude, like No. 2, is far more of a piece than most of the others; its whirring 32nds are interrupted notably only once, by heady glissandos followed by trills. These mark the only forte until the end of the piece as well. Note values otherwise shift only from very fast duplets to very fast triplets and even the meter shift from2/4 to 3/4in m. 54, with its newly encountered bass melody, feels integrated. The piece whips itself around with the skill of a magician, and at the end, the magician grins knowingly and plucks his last note very softly --as if to say that all the preceding was smoke and mirrors, and all that really exists is this last pianissimo 8th note.

No. 7, Pour les degrees chromatiques, seems to me to mark the reappearance of Puck in La danse de Puck and the fairies of Les fees sont d’exquises danceuses from Preludes, Book I and 11. Debussy must have missed their “sly malice!” This music is similarly airborne, flying through high registers, delighting in mischievous dotted rhythms, and zooming in for an earthly landing only in the very last bars. Almost the entire piece is played at piano or below; the fairies are plotting in whispers.

No. 8, Pour les agréments, epitomizes the willingness to undermine every statement with a contrary statement that characterizes both the Commedia and late Debussy. Debussy oscillates between the exquisite embellishments of the opening and the carnival material abruptly introduced in m. 21. The next 20 measures, until the opening returns, constantly teeter between a grave, delicate elegance and a bumptious vaudeville romp. This is one of the most melodious of the etudes, but the melodies are always in flux: the opening 32nd note idea gives birth to melodic ideas so dissimilar that the listener is hard pressed to associate them, let alone hear them in close proximity. As in Etude No. 1, the line is blurry here between comedy and serious theater, but both seem to amicably tolerate life with the other.

No. 9, Pour les notes répétées, Even the premise of this etude is perverse, for all those extra repetitions are just a stunt – we would have heard the melody just fine had every note been played only once! The music is appropriately jerky, stopping and starting, and proceeding in fits and starts. It generally smiles on the world, but shifts its vantage points from that of a slightly irascible marionette in the opening to that of a lyrical string player, first in m. 28, then again in 55 and 58. There are strident outbreaks along the way – this etude is the antithesis of smoothness – but the end is reassuring; it saunters to a carefree close, announcing again that everyone involved has come to a friendly understanding.

In No. 10, Pour les sonorities opposés, the music starts out in an eerie- almost-Schoenbergian universe of dissonance. It’s the only etude to begin in slow outer space, and it banishes the nervous energy of the previous piece entirely. We hear immediately that the piece will be about both opposing sonorities and opposing registers, or opposites colliding. The low gongs which pervade the opening follow us through much of the piece, and the crossed hands first indicated in m. 7 are also omnipresent, signaling perhaps a physical crossing of opposing fields. Strangely out of place in this mysterious universe, a pert dotted-rhythm figure manages to escape the overriding solemnity (m. 31), and it refuses thereafter to be banished completely. We forget its insouciance while attending to the next episode, an increasingly impassioned tenor melody again played with crossed hands, but it is intrepid, returning twice more and dominating the ending. Even in the midst of this intense gravity, Debussy’s joker makes himself known.

Likewise in Etude No. 11, Pour les arpèges composés, the delicacy of the music, so firmly established by cascades of sensual arpeggios, is eventually displaced by burlesque humor. The first hint appears in m. 25 when the heretofore seamless flow of notes is interrupted by a rest and a quick fortissimo upward spiral. The staccatos and marcatos and “un poco pomposo” of m. 25-28 then prepare us for the “giocoso” section beginning in m. 29, where the music stops and starts unpredictably and appears to delight in being disrupted. We lurch along with it, taking the bumps in good humor, but wondering whatever became of that “dolce e lusingando” we’d been primed for at the beginning. It returns, though not entirely unscathed – a somewhat chastened clown makes his presence felt again in m. 58 and 60. Once again, an armistice between opposing aesthetics has been arranged, and in this case, the clown has been subdued and finally put to sleep.

No. 12, Pour les accords, is bombastic, almost diabolical in its rhythmical trickery. Its plays on 6/8 bring “Masques” to mind, but here the knavery has upped the ante. Only in Brahms had 6/8 meter previously met so many incarnations, and Brahms wasn’t nearly as roguish about it. For one thing, he didn’t make pianists jump around on the piano as if it were their private trampoline; Banville’s exhortations to his clown to jump higher, ever higher ring very true here! For another, Brahms provided a smoother ride; energy levels didn’t zoom from maximum to minimum with barely a transitional gear in between. Debussy’s hard-pressed athlete finds himself floating amidst barely-moving static harmonies in the middle of the piece just as he’d warmed up his speediest act. He gets to start jumping again, though – if Debussy had known Energizer Bunnies he might have welcomed them into this steely Commedia!